The rich history of the Black American cowboy is part and parcel of the American West.

Written by Constance Dunn

The year was 1865. The American Civil War was over, and the just-signed 13th Amendment outlawed slavery. The frontier states of the America West, with their potentially rich store of opportunities, were a lure to many black Americans, most of them newly freed slaves. Among the options for work—particularly if one had experience with livestock and could rope or break a horse—was working on a Western ranch or joining one of the near-constant cattle drives originating in Texas.

According to Larry Callies, founder of The Black Cowboy Museum, located in Rosenberg, Texas (about an hour outside Houston), and whose Texan family cowboy roots reach back to the 1700s, cowboys embodied and lived a resilient, go-it-alone attitude in an oft-dangerous natural environment—and the word itself is a tip-off to the prevalence of black men among their ranks. “The cowboy was honest. The cowboy was alone. The cowboy was tough,” he says. “The cowboy could fight. And when I’m talking about the cowboy, I’m talking about the black cowboy.” That’s because white cowboys, he puts forth, were not initially referred to as cowboys, but as cowhands. “When you said ‘cowboys’ in Texas, they were talking about freed slaves,” Callies explains. “The white man wasn’t called a cowboy. He didn’t want to be a servant.”

The actual number of black cowboys in the American West is unknown, with estimates ranging anywhere from 25 to 35 percent of all cowboys. Callie, however, pegs the number as much higher. “If you saw a team of cowboys, one or two were white,” he says. “The rest were black.” No matter the number, what is clear is that the presence of the black cowboy has not been adequately reflected in history books or popular culture. “They left us out of the movies, completely,” notes Callies. “They left us out of history, completely.”

“There were black cowboys, and they were important. Their life is not going to go in vain.”

— Larry Callies, founder of The Black Cowboy Museum

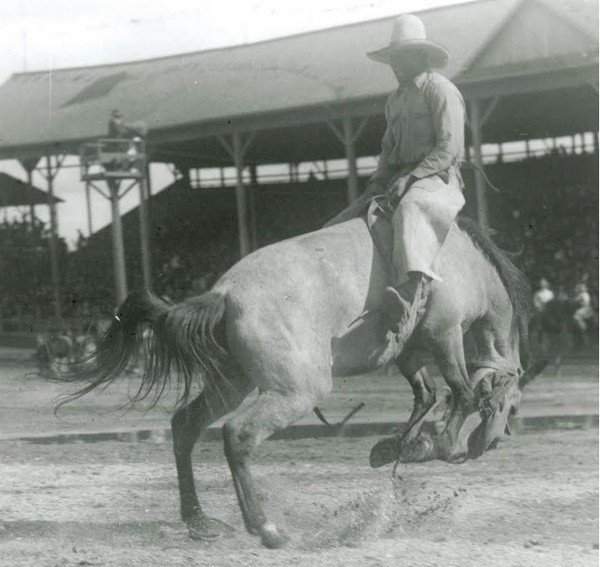

In the realm of the American West circa the 1800s, there were black cowboys that were famous as well as infamous. Among the most notable figures is lawman extraordinaire Bass Reeves, a U.S. Marshal appointed in 1875 whose jurisdiction was the rough Oklahoma Territory, and whose relentless pursuit of outlaws remains the stuff of legends. Famed rodeo competitor Jesse Stahl who, in response to garnering second place when a first-place win was clearly in order, rode an unruly bronc backwards—with a suitcase in hand. Famed cowboy Nat Love, also known as Deadwood Dick, was a former slave from Tennessee whose Western exploits started in his teens after he joined up with a cattle team in Dodge City, Kansas. Love’s vivid chronicles are captured in his 1907 memoirs, “The Life and Adventures of Nat Love, Better Known in the Cattle Country as ‘Deadwood Dick.’”

By the late 1890s, an increasingly populated American West and the rise of industrialism—notably railroads that took over the shipping of cattle to market from cowboys—forever changed the Western landscape, and with it, the need for a great number of cowboys. Their numbers, black and white alike, dwindled.

In the words of Nat Love (from “The Life and Adventures of Nat Love. Better Known in the Cattle Country as ‘Deadwood Dick’”):

“To us wild cowboys of the range, used to the wild and unrestricted life of the boundless plains, the new order of things did not appeal, and many of us became disgusted and quit the wild life for the pursuits of our more civilized brother. I was among that number and in 1890 I bid farewell to the life which I had followed for over twenty years.”

Just as the spirit, traits and values of the American cowboy live on—with that trademark dedication to both the individual and collective that shaped him in the 1800s—so does the black cowboy, whether in the plains and prairies, or transposed to modern-day scenes of steel and concrete. “When I put that cowboy hat on and step into the world,” says Randy Hook of youth horse ranch Compton Cowboys in Los Angeles County: “people see me and think, ‘He’s a man who understands the importance of being in harmony with nature. The importance of setting a good example for the next generation of kids. The importance of working hard and building—and not being afraid to go forward, get off the beaten path and establish something.”